Foreign Language Learning While You Sleep?

(Updated 9/22/2017)

(Updated 9/22/2017)

Have you dreamed about leaning a foreign language during your sleep? I certainly have.

Just imagine, a few electrodes attached to your head will infuse your brain with a new language while you sleep. Unfortunately, it's still science fiction stuff: A nice idea, but clearly not yet realistic at this time!

On the other hand, Swiss scientists have proven with a number of tests that you can indeed enhance your vocabulary retention during sleep. At least it's a start. I first found this on PsychCrunch's podcast Episode 5: How to Learn a New Language, which includes an interview with Professor Björn Rasch from the University of Fribourg, Switzerland.

I contacted Professor Rasch and he was kind enough to send me three articles, the latest one titled: “The beneficial role of memory reactivation for language learning during sleep: A review,” authored by him and Thomas Schreiner. (The article is available now on Elsevier.com's “Brain and Language” and can also be obtained via ScienceDirect.)

Language Learning Stages

I found the Schreiner/Rasch article fascinating because it examines the close tie between language learning and the basic processes of memory. As you learn words in a new language, you go through three core stages: encoding, consolidation, and retrieval.

Encoding

When we first hear new words (also called labels) for objects, activities,  feelings, etc. in a foreign language, our brain has to encode them. That means, we change the information into a form that our memory can cope with.

feelings, etc. in a foreign language, our brain has to encode them. That means, we change the information into a form that our memory can cope with.

There are three main ways in which information can be encoded:

• with a picture (visual)

• with sound (acoustic)

• with meaning (semantic).

For example, to learn the German word for “dog,” you could use an image of a dog plus the audio and/or written text “Hund.” That's the encoding.

The authors remind us that, “during encoding, new and initially labile memory traces are formed that are still highly susceptible to interference.” Nevertheless, such “memory traces” are no longer just conjecture. They can be made visible today with MRI brain scans.

Consolidation

During this stage, the newly encoded memories are “stabilized and strengthened” and “gradually integrated into pre-existing knowledge networks on the cortical level for long-term storage.”

This must be the stage where practice and interactive learning comes into play. Whether by associations with images or feelings, repeating and saying aloud, spaced-recall exercises, writing, or other drills - consolidating new memories is essential for learning a foreign language.

It's especially at this stage that sleep is key. Before reading the article, I was not aware of how important sleep is for memory functions. Schreiner/Rasch note: “While encoding and retrieval are clearly tied to wakefulness, sleep plays a crucial role in the consolidation of newly encoded memories. There is a vast amount of research that documents the beneficial effects that sleep has on memory.

Retrieval

In this third stage, memories can be accessed and are available for active use. We know what that means when we start practicing a foreign language: We not only understand the meaning of the foreign words, we can also use and apply them when listening, reading, speaking, or writing.

In this third stage, memories can be accessed and are available for active use. We know what that means when we start practicing a foreign language: We not only understand the meaning of the foreign words, we can also use and apply them when listening, reading, speaking, or writing.

Understandably, the memories stored in our brain are more like a collage, or even a jigsaw puzzle, than a series of lists. And thus, associations (helped by context, specific questions, or other cues) play an important role in the retrieval of information.

(I was recently made aware of an article, 4 Crazy Things We Misunderstand About Human Memory, which is quite relevant to this subject. In fact, many of the article's conclusions - how to better remember things - we also advocate and can help your language learning: writing words down, making audio recordings, creating visual prompts with Post-It notes, associating things with imagery. )

Sleep/Language Study Set-up

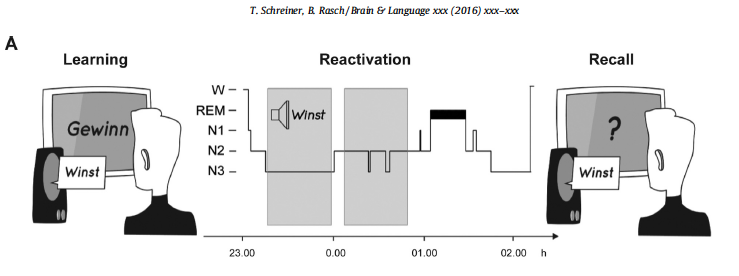

A group of Germans was given 120 Dutch-German word pairs to study before 10 PM. Then, half of the group, the “Sleep Group,” slept for three hours, while the other half, the “Control Group,” stayed awake.

The Sleep Group heard a portion of the words - referred to as “cued” words - during their sleep, but during their “Non -rapid eye movement” (NREM) sleep, which typically occurs during the first few hours when you do not dream.

The same words were replayed to the Control Group. After three hours both groups were given tests. The Sleep Group had better recall of the (“cued”) words they had heard during sleep than the Control Group who had listened to them while awake

The image A above shows the set-up and when the Sleep Group heard the “cued” Dutch words.

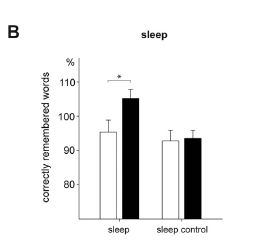

Graph (B) shows that in the Sleep Group, recall for the German translation  of the cued Dutch words (black bar) was significantly improved when compared with uncued words (white bar).

of the cued Dutch words (black bar) was significantly improved when compared with uncued words (white bar).

In the Control Group, there was no significant difference between the recall of cued and uncued words.

There are more study details and observations by the researchers than can be discussed here (including the cueing timing and intervals).

The study seemed to confirm that verbal cues – e.g. replaying during sleep a list of foreign words that had been learned earlier – can reactivate the memory of those words.

In other words, hearing vocabulary during our sleep could greatly enhance the “consolidation stage” of our memory and thereby the language learning process.

Conclusions

The authors note that “the findings reviewed above demonstrate the crucial role of sleep in language and specifically word learning.

It has been shown that sleep promotes divers aspects of language learning, from word learning to the abstraction of grammar rules (Batterink et al., 2014; Henderson et al., 2012) and possibly constitutes an ideal state in order to facilitate and accelerate distinct learning processes.

In this vein, evidence that foreign vocabulary are capable of inducing such reactivation processes and thereby enhance subsequent memory performance critically broadens the scope of cued memory reactivations during sleep.”

Open Questions

Schreiner/Rasch also acknowledge a number of open questions. Among them:

• What would be the consequences when the word cues were heard during REM sleep (vs. NREM sleep)?

• Do closely related languages (e.g. Dutch/German) make cueing during sleep more effective?

• Does cueing affect sleep quality?

We would also ask:

• What is the optimum timing sequence?

• What is the optimum audio volume level?

• What about phrases and sentences vs. individual words?

There is clearly still more research needed to determine how best we can take advantage of these findings in language learning practice at home.

One Practical Take-Away

After reading the study and understanding more about the importance of sleep for the “consolidation stage” of our memory, I have set myself a new goal: Play one of our Spanish lessons or Quick Games before turning off the lights.

Finding a way to “cue” the right words at the right time at night, will certainly be a little more difficult. But it may also be the next frontier that language learning companies will want to cross.

Bio: Peter Rettig is the co-founder of Gamesforlanguage.com. He is a lifelong language learner, growing up in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland. You can follow him on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, and leave any comments with contact.

References: Schreiner, T., & Rasch, B. The beneficial role of memory reactivation for language learning during sleep: A review. Brain &Language (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bandl.2016.02.005